TIME beat me to it when it unveiled their annual 100 Most Influential People of 2017 list featuring, amongst others movers and shakers, the Chobani CEO fellow Turk (and Kurd) Hamdi Ulukaya.

Hamdi Ulukaya puts the xenophobes to shame,” Kenneth Roth, executive director of Human Rights Watch, wrote for Time. “At a time when some accuse immigrants of stealing jobs, the Chobani CEO – a Kurd born in Turkey who moved to the US in 1994 – is creating them, big time.”

“Hamdi personifies the American Dream, showing that anyone arriving on US shores with drive and intelligence can make it – and bring others along with him,” Roth stated.

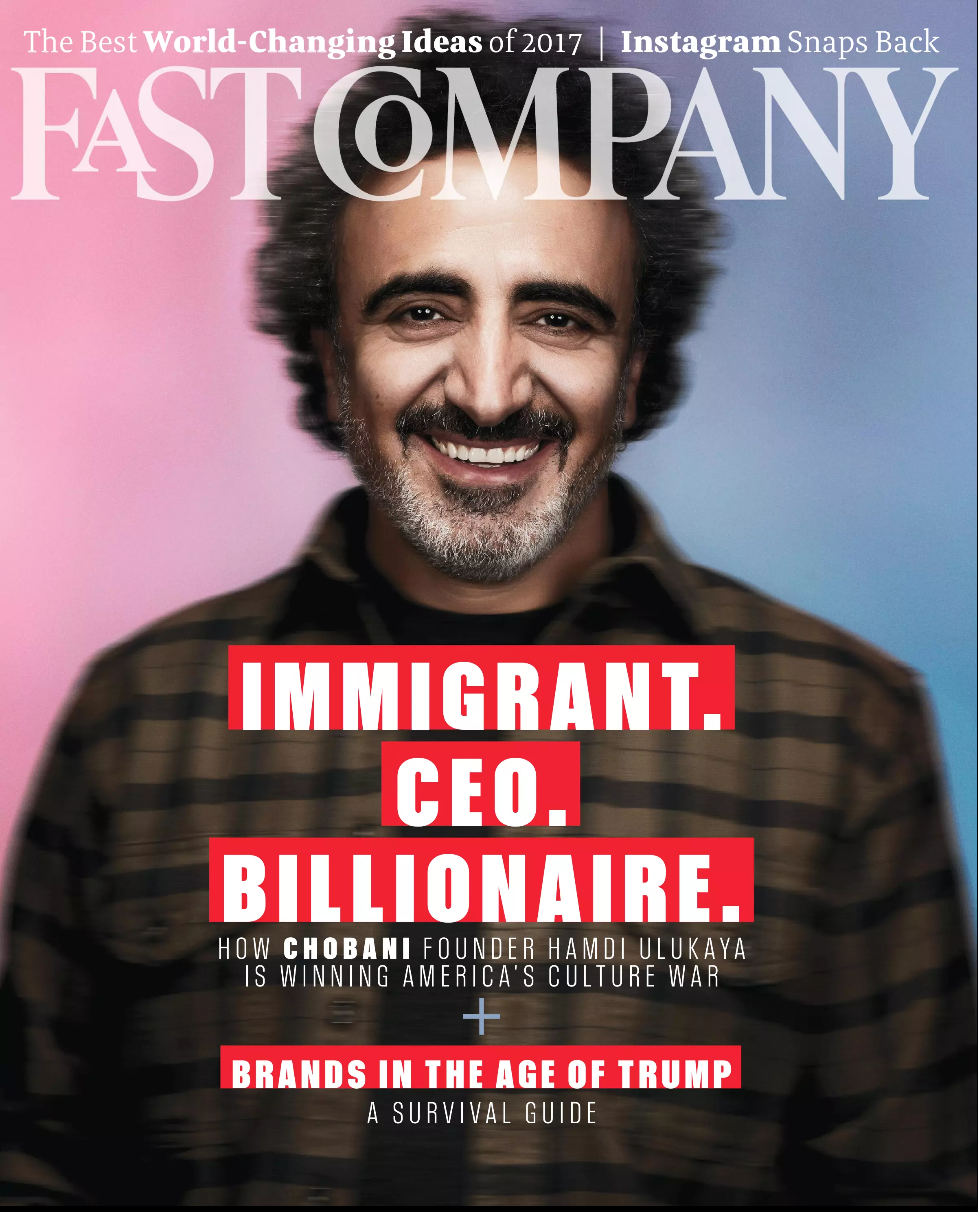

I had of course heard the name of this philantrophic businessman who hails from the back of the beyond in Turkey and is in some ways the epitome of the American Dream. After I read his profile which was the cover story of Fast Company’s April edition, I have a new found respect for Ulukaya.

Better late than never, I bring you all that you need to know about this magnificent Turk.

He’s a shepherd boy

Hamdi Ulukaya was born in 1972 to a Kurdish family in eastern Turkey’s Erzincan province where his family raised sheep and goats and made Tulum cheese. They lived a nomadic life spending winters in Iliç, a tiny town near the Euphrates River accessible only by a train that ran through twice a day, and in warmer season moved to the Munzur mountains with their flock, roaming the high meadows and sending cheese back on horseback to trade or sell.

He is an accidental refugee

While studying political science at Ankara University in the early 1990s, Ulukaya was had gravitated toward the contentious Kurdish-rights movement, attending demonstrations and publishing a politically minded newspaper. Though he wasn’t involved with the extremist group the PKK, he nevertheless attracted the attention of the Turkish government. He knew he had to leave. While he considered Europe as an option, “I didn’t know anything about America,” Ulukaya recalls in his interview with Fast Company.

Advised by a friend to think about the US, in October 1994, Ulukaya arrived in New York City, with a small suitcase and $3,000 for living expenses which lasted only a month. He transferred to New York’s public Baruch College, supporting himself by working for an Armenian rug merchant and pumping gas at a Brooklyn filling station.

He is an unlikely capitalist

An anti-capitalist immigrant, after years selling feta cheese, Ulukaya turned his attention dominates the $3.6 billion Greek yogurt industry, besting international conglomerates such as Danone and General Mills.

While studying English, when he wrote about making cheese back at home, Ulukaya found outabout farms in America through a teacher who had a farm upstate. He persuaded his teacher to give him a job on the farm, milking cows and shoveling manure. He moved nearby and enrolled at SUNY Albany.

It was in 1995 when his brother one of his five brothers, Bilal, moved from Turkey to join him upstate, followed their father who came over for a visit the idea of a business took shape. Not keen on the American feta cheese, their father suggested importing cheese from back home. While the plan didn’t make financial sense, making their own cheese did. In 2002, using seed money from family members, the brothers launched a little feta cheese company called Euphrates in Johnstown, New York.

Going into yogurt business was another chance discovery for the accidental businessman. Working late one night, he happened on a real estate flyer he had chucked in the trash advertising a fully equipped yogurt plant for sale. A light switch had turned on – could he possibly make business out of the strained yogurt he made at home?

After receiving a Small Business Administration loan of$800,000, he purchased a defunct Kraft foods plant in upstate New York which birthed Chobani, now the largest yogurt brand in the US.

In just a few years, Chobani went from selling a few containers at a Long Island kosher grocery to being the No. 1 selling yogurt brand in the country with annual revenue topping $1.5 billion. Chobani now owns 36% of all Greek yogurt sales—a category that barely existed before Ulukaya came along and today accounts for 46% of yogurt purchases.

He is the CEO that keeps on giving

In April last year, he announced that he was giving his employees a 10% share in the enterprise, making some of the workers millionaires overnight.

“How we built this company matters to me, but how we grow it matters even more. I want you not only to be a part of this growth – I want you to be the driving force of it,” Ulukaya wrote to his employees at the time.

He also employs more than 400 refugees –about 30% of the company’s 2,000 employees – a decision which has attracted calls to boycott his products, racial epithets on social media, and conspiracy theory articles posted to right-wing media websites like Breibart News.

This hiring strategy began in 2010 when Ulukaya called on Mohawk Valley Resource Center for Refugees in Utica, New York. When Chobani opened its Idaho plant, upon discovering that Twin Falls is also a big relocation destination, Ulukaya deployed the blueprint established in South Edmeston here.

Speaking about his support for refugees, Ulukaya told Fast Company, “I built a $450 million plant and all that stuff, but the part I love the most is becoming this hub for building lives. Refugees have gone through so much… And seeing them smile and full of energy, it’s like a new world is created—while you’re making a cup of yogurt! Nothing is more beautiful than that.”

Not only has he committed himself to Warren Buffett’s “Giving Pledge” promising to donate at least half of his wealth to charity, to that end, he also founded an organisation called Tent, which assists refugees in achieving new lives. More than 70 companies —including Airbnb, Cisco, IBM, Unilever, and UPS — have signed up for the Tent Partnership for Refugees, agreeing to donate resources and hire displaced people, among other efforts.

He has built a clean and fair brand

Chobani products are all-natural: no preservatives, only non-GMO ingredients, milk from cows not treated with the bovine growth hormone rBST.

The company has also always given 10% of its profits to charitable causes and community projects, such as a public baseball field near his upstate New York plant Ulukaya renovated in 2011.

Chobani also pays above-average wages, and that new family-leave policy offers full pay for any new parent, including foster and adoptive parents.

Ulukaya has stated that higher wages for employees leads to greater corporate success. Not only does he promote the position that companies can succeed when they pay their workers more, they also have a moral obligation to do so, stating that, “…for the sake of our communities and our people, we need to give other companies the ability to create a better life for more people.”

Ulukaya has put a great deal of thought into cultivating a spirit of warmth and enthusiasm in his factories. “To me, there are two kinds of people in this world,” he told The New York Times. “The people who work at Chobani and the people who don’t.”

He is a warrior

“I’m a shepherd and I’m a warrior,” he says about the two sides of his personality in his Fast Company interview. “I come and go between those two. I’m a nomad, and nomads are the most real people. You can’t pretend.”

“I hate my competitors,” Ulukaya adds. “I have to create an enemy, and I have to get rid of it, in a metaphoric way. I don’t hate people; I hate the idea. We hate Big Food.”

Last year he took on the competition with a series of commercials artificial ingredients used in some Dannon and Yoplait yogurts.

Ulukaya also fought the system as well as the competition. His first move was to offer alternative packaging to the untrained American yogurt buyer: European-style tubs, which are shorter and wider than American cups, with logo and product info printed on colored plastic sleeves as opposed to on the cup itself.

Hen then fought for distribution. As the business grew, Ulukaya insisted on placing his products next to the familiar megabrands in the regular dairy case as opposed to the the organic specialty aisle—where imported (and more expensive) Greek yogurt was usually hidden away. A hard sell which eventually worked out when early believers such as Fairway and ShopRite discovered that when they followed Ulukaya’s strategy, Chobani tubs really moved.

Ulukaya’s early business approach included strategies the larger companies did not use. Rather than pay stores a slotting fee, which his start-up company could not afford, he paid stores in yogurt rather than in cash to stock his wares. He also negotiated to pay off the slotting fees over time as the yogurt sold. He also implemented in-store samples so customers could taste the product and purchase it immediately.

Lacking the budget for traditional marketing, after hearing customers phoning in to say that they loved Chobani, Ulukaya had his small team reach out to bloggers, Facebook, and Twitter to have constant and direct communication with consumers.

In 2010 he also created a sampling truck, the CHOmobile, which handed out free cups of Chobani yogurt at festivals, parades, and other family-friendly events all over the US. In its first year, the sample truck gave away 150,000 full-size containers of Chobani.

Once the tubs began shifting, it was all about making more. For the next five years Ulukaya barely left the plant. “I don’t remember anything I did—day or night—that wasn’t related to yogurt,” said Ulukaya in his Fast Company interview.

Between 2008 and 2012, the South Edmeston plant grew to 600 employees, cranking out as much as 2 million cases of yogurt per week. Chobani sold $1 billion worth of product in 2012.

He is brave in his journey

From the humble beginnings of Chobani, Ulukaya has been approached by suitors who wanted a share in the business and has chosen to go it alone. The most recent offer was from PepsiCo in 2016 seeking a majority share which Ulukaya turned down.

“They wanted to have control,” he told Fast Company “Without going into details, that [would be] the end of Chobani. This company has never been controlled. It’s the same with me: If you put boundaries around me, I’ll try to break it. Chobani has always been free. And in that freedom, it will do the right thing.”

He is a dreamer and a doer

There is no denying Ulukaya is the American Dream personified – a Kurdish shepherd boy from eastern Turkey making it big in America. He had a dream and he made it happen. He is now on to bigger dreams. Chobani is now aiming beyond their core products and eyeing up international markets. One exciting area of expansion is Chobani’s cafés, where you can enjoy exclusive yogurt concoctions (both sweet and savory) as well as Turkish-style simit sandwiches and other items.

CMO Peter McGuinness wants people to think of Chobani as “a health and wellness company: It can be what you eat, how you act, how you treat people in the workplace—it’s a larger idea.”

No doubt, Ulukaya will make that happen too.